(A Tragedy in the Key of Bourbon Minor)

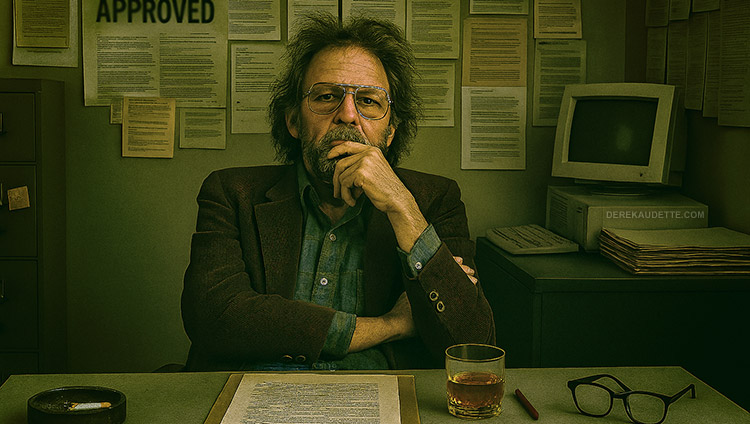

There are bureaucratic errors that get corrected, and then there are people like Eliphas Plunk — clerical oddities of existence on which somebody, somewhere, stamped approved out of blind fatigue. He was the human equivalent of a form filed in triplicate and lost in the mail; a man who arrived at life without a manual and kept insisting the missing pages were art. He looked like a person who had once been promising but then decided the bratwurst of destiny was overrated and took up a more contemplative hobby: blinking. And, dear God! Eliphas Plunk! Who gave him that name? Probably some parent, or something.

If you are the sort to romanticise failure, Eliphas will disappoint you by being too competent at it. He failed with panache, yes, but he failed reliably, faithfully, as though he had a paid subscription to ballsing everything up. Love, career, small domestic rituals — each was a ritualised misfire in which he performed his lack of interest expertly until it became character. He wrote poems that tasted like cigarette ash and old beer; he taught a class on underachievement and received a grant from someone who mistook it for performance art. Later this would be called the Plunkian Method and interpreted variously by critics and subscribers to at least one email list.

He liked the cadence of long words because they made him feel like he had done something. “Transcendental” sounded more meaningful than “tired,” “ephemeral” more invested than “temporary.” He loved epithets—those ornate bandages people use to pretend a wound is decorative—and he collected them as consolation prizes. People sometimes called him “enigmatic.” He pretended not to notice. Every once in a while he pretended to notice deliberately, like a con man checking his reflection.

I. On the Art of Rising (Because Someone Has To)

One morning — or something approximate to a morning; Eliphas had never been rigorous about calendars — he woke to the white, uninterested face of his ceiling, which looked to him somehow like a judge that had fallen asleep on the bench— or, at least, it evoked that image in his mind. The apartment smelled of stale revelation: last night’s bourbon negotiated with yesterday’s ambition. The bottle, that old, honest lobbyist for oblivion, sat like a benign sentinel. He drank because he could not think of a better verb.

He rose and moved through the room with the solemnity of a man making amends for transgressions he did not remember committing. There are gestures people make as ritual: brushing teeth, tying shoelaces, apologising to the neighbours. Eliphas had rituals too. He cursed at his shoes, which were every bit as thin as his philosophy and twice as brittle. He made a show of straightening the collar of a coat that had given up on representing any sort of respectable style long ago. He surveyed the mirror and addressed the stranger he saw in it. “There you are,” he said, with the kind of fond contempt reserved for bad performers who don’t have the common decency not to show up to the gig.

There is a special, private terror in acknowledging your shape in the mirror and not recognising the story it insists you are living. Eliphas had reconciled with this terror months ago by making it an aesthetic. He decided to be an artist of the quotidian, a curator of small, repeated mistakes. If life would not give him meaning, he would craft an aesthetic: decorous malaise. He liked the sound of it, as one naturally likes the sound of any phrase that absolves one of effort.

II. The Gallery of Deferred Catastrophes

He drifted to a gallery that afternoon — a small, officially damp cathedral — because galleries are where culture puts all its undecided feelings on display. And, not much bored Eliphas more than feelings that had been decided. The walls were white and suspicious; the air smelled like the inside of an old mass-market paperback and mild disappointment. He set a glass down on a donated pedestal and called the faint, watery ring around it Portrait of Ennui #7. The curator, someone who had long ago learned the economy of nodding correctly, pronounced the piece “a study in negative affective resonance.”

The words meant nothing and everything. People nodded. A woman sniffed and said, “It feels like absence rendered visible.” Eliphas considered informing her that he had washed the glass only once in three months, but decided that would ruin a good misunderstanding. Misinterpretation, he knew, was the currency of art.

He basked in the sliver of social oxygen granted to pseudo-profoundness. It tasted almost like realness: slightly metallic, faintly antiseptic, but still a little sweet. He walked about the gallery like an actor who had accidentally stumbled into the climax of the play and decided to stay for the curtain call.

Clara met him there, resplendent in the kind of sincerity that frightens clever men. She was not a thief of objects but of trajectories; she stole possibility with a smile. Every angle she played she had lifted out of someone else’s pocket or purse when they weren’t looking. “You make absence seem considered,” she said, meaning something that would later require a team of taxonomists to decipher. He delighted in this because it gave him the illusion of having engineered his inertia. She said she wanted to teach forgiveness for a living. He said he had once taught a class on tolerance for minor inconveniences. They kissed, exchanged books that neither of them would ever read, and went on to adopt a ritual of making small, performative attempts at improvement. She did yoga. He attempted to be supportive, which is to say he sat in the corner and smiled in a way that suggested philosophical approval.

III. The Love That Was Practically a Fund Raising Opportunity

If Eliphas had a mode of courting, it was mostly improvisational and slightly panicked. When Clara presented him with possibilities, he bribed himself with tiny reforms: better shampoo, the occasional dusting, a book shelved upright—spine facing out. Love, to him, felt like a loan with no maturity date; he appreciated the cash flow but feared the amortization.

The relationship had the momentum of a theatre troupe rehearsing a tragedy, which is to say it was performative and low-budget, and in the end, sad—always destined to conclude badly. They were a duet of near-miss commitments, an operetta about starch and stomach-linings and the mouldy end-piece of a hunk of old cheese. She would ask him to be honest; he would craft a truth slightly smaller than she expected and pass it off as candor. “Are you happy, Eliphas?” she asked once, in the voice people use to invite confessions. “Happiness,” he said, “seems like a full-time job. I’m working part-time these days. But, yeah, sure. On my days off I’m happy enough, I suppose.”

Then she left; because people rarely stay for the sequel when Act One has been this whiny and tough to sit through. She took the plants, the incense, and a potted hope that had been languishing on the windowsill. He kept an old chair and the television remote, along with most of everything else—which wasn’t all that much… but still more than nothing—which was less than what Eliphas thought he deserved.

When she left, Eliphas discovered that heartbreak is mostly an organizational problem. You have to inventory the pieces and decide which are salvageable. He was practical in his grief: he named the things that were replaceable and made a comforting list—job, relationship, dignity—then crossed out dignity because it had been overdue on payments as of late.

IV. Teaching the Young to Underperform with Style

An adjunct program at a local college invited him to teach a night course titled Creative Apathy and the Ethics of Small Failures. He accepted out of curiosity and, admittedly, an unaccountable need for an honest paycheck. The class was populated by undergraduates who wanted authenticity like they wanted filters and limitations: as a commodity.

Eliphas arrived with a syllabus that was half aphorisms, half quotes lifted from philosophers who looked dour in portraits. He told them inspiration was a marketing tool for mattress stores. He taught them to savour the productive lethargy: “There is virtue in conserving disappointment,” he lectured, which is to say he gave them permission to stop performing busy. And, oh how they did.

The students adored him. They wrote essays about his detachment and sent messages afterward that read like invitations to a cult devoted to the worship of 1950’s era graphic design aesthetics. Someone even made a zine. Someone else started a podcast called Underachievers Anonymous. One student proposed a thesis on “Plunkian Minimalism.” Eliphas was flattered as a toaster might be flattered at being called the greatest thing to toast the greatest thing since sliced bread.

But fame can be highly combustible in the wrong hands, or if held too close to a match or stuffed inside a flattered toaster. A young critic misread his mood as irony and an editor offered him a column promising him a small stipend to be a “voice of a generation that doesn’t want to try.” Eliphas accepted, then panicked. Success felt like the arrival of a storm you had put off building an ark for; he fled by writing a manifesto on remaining comfortably small. The piece went viral to the extent such things do — a hundred people shared it with captions like, Finally, someone who gets me! and This guy knows what’s up! He felt both admired and mildly exposed. He kept his resignation letter from the adjunct office in a drawer as a talisman against escalation.

V. The Vessel, the Riddle, the Long, Damp Night in the Underpass

The city is a palimpsest of good decisions written over worse ones, crossed out and then doodled over with inept drawings of stick figures and malformed cats . In one of those marginal days, an old woman — a fixture between bins and subway timetables — approached him with a brown paper bag and a proposition that smelled of fate and something like stale pastry. “There is a thing,” she croaked, peering through spectacles that had seen nations of pigeons rise and fall, “a vessel that will return to you what you’ve misplaced.”

Eliphas thought this must either be a scam or a plot point and thought to himself that both sounded equally worthwhile. The woman directed him toward the river’s forgotten culvert, the kind of subterranean architecture where the pigeons hold philosophical debates about the true nature of bread. There, under a rain smell and a map of leaks, he found a tarnished goblet bearing an etching of an ape’s face, a pub spoilsman’s joke reserved for late-night clinking. It glinted in the moonlight like a poor man’s relic.

A drifter guarding the tunnel — a man named Robert who had the pleasant habit of speaking in riddles and the unfortunate habit of being sincere — demanded an answer to proceed. “What has locks but no doors, expanse but no room, and admission without entry?” he intoned in a voice bored into the concrete. Eliphas was tired and answered with the instinct of someone who has been taught too many trivial things in his life. “A keyboard,” he said, merely because he liked the way the word landed.

Robert sighed with the expression of someone who had been risen from a night’s sleep to find that someone else had already done his favourite crossword puzzle. He allowed Eliphas passage and warned him with the solemnity of a fortune cookie: “The vessel will grant and subtract in turns. Beware its calculus.”

Eliphas drank from the goblet because protagonists in stories often drink from goblets and because the tavern of hope had, for the day, run out of options. The draught tasted of pennies and rain. It gave him a brief clarity: colour sharpened, sounds had a halo, the city’s cruelty seemed momentarily intelligible. He wandered back into daylight and almost immediately found a wallet full of cash. He returned it to a flummoxed merchant and received a respectable reward. He discovered that an obscure friend actually loved his small poems. He was offered, and took, a job promoting a low-budget art event and, for an afternoon at least, he actually felt fertile.

Then the vessel cracked — a hairline fracture that let through a beam of misfortune like a leaky faucet lets through small, relentless, watery inconveniences. The reward money was misplaced. The job folded under someone else’s irresponsibility. Daisy, the old woman from the subway, who had the grin of a rusty weather vane and the morals of a bargain bin, reappeared just long enough to take lunch and a fair dose Eliphas’s cynicism. Eliphas learned from her the arithmetic of the goblet: it granted coin to borrow and interest to despair. He returned it, clumsily, to its damp altar and muttered thanks in the way one might thank a thunderstorm for not being a tornado.

VI. The Performance, the Fire, the Rediscovery

There came a night — inevitable and theatrical and smelling of smoked paprika — when Eliphas mounted a platform under a bridge with Ziggy, a busker who played guitar like a man trying to resurrect a lost civilization. They performed for a crowd of the mildly curious: drifters, punters, two policemen who had missed their beat and had yet to pick up their rhythm, and a young couple looking everywhere for some subtext they’d somehow misplaced. Eliphas declaimed a piece that folded philosophy into bad jokes; Ziggy riffed on the sort of chords that make people remember the voluptuous ache of living.

The set ended with applause and the sort of intimacy public spaces offer: brief, gleaming, and cheap. Then, in true farcical tradition, a rival performer — a man with a habit of brandishing dull knives and sharp resentment — shorted the amp. Electricity arced, a smell like burnt offerings filled the air, and someone, in all of the bedlam and confusion, knocked over a candle. Flames took hold like hot gossip. They spilled out onto the crowd in a hungry, foolish way.

Eliphas, who had never been particularly brave, found himself operating with the austere competence of amateur heroism. He grabbed a fire extinguisher and sprayed foam like a man giving an impassioned lecture on the unique stench of panic. People stumbled, shouted, saved the guitar, saved nothing of substance, and saved each other in ways that felt mildly awkward and more than a little uncomfortable. The venue was wrecked; the patrons shook their heads and called it an event. One for the books! One to remember! And, despite the odds, quite a few actually did.

Afterwards, with soot in their hair and adrenaline leaking from their pores, the crew found they had something like a myth on their hands: the story of the night when the misfits nearly set the world on fire but didn’t quite finish the job. They celebrated with toast from a flattered toaster and a small wagon of cheap pastries. In the morning, repairs were made, concerts were cancelled, and Eliphas found a note under a bench that said simply, You were good, man. Real good. He folded the note into a pocket and carried it more like a fossil than a trophy.

VII. Reputations and the Strange Economy of Shame

Time rearranged itself for him into a pattern: small moments of near-success smudged by some petty misfortune. His online following grew in an odd way: people admired the authenticity of a man who was convincingly tired. He was invited to write, to speak, to sign copies of things he’d written, or sometimes hadn’t. He declined some offers out of principle, accepted a few others out of curiosity, and bungled everything with an offhand chapbook of collected aphorisms and anaphorisms. The critics called it “a mordant voice for the unmoored and unmordant.” He took the compliment and filed it— alphabetically at first, but in time, not so much.

When the world asked for definitions, Eliphas supplied approximations. When it asked for approximations, he supplied improbabilities. He titled an essay On Holding Your Breath While Life Rearranges Your Furniture. It circulated with the sort of modest virality that begets other people’s wildly inaccurate interpretations. There were think pieces written by people who liked to compare cultural malaise to coffee preferences. He found himself pleased by how willing the world was to mythologize ambivalence.

Then the fire, the goblet, the gallery — all the small events folded together like a road map that proves difficult to fold together. He found himself subject to a new, gentler vocabulary: cult favourite, local legend, oddly sincere. He laughed once while attending a public event and found himself recorded and quoted as if the laugh were an argument for the veracity of some profound notion.

VIII. The Quiet Afterword

When Eliphas finally died, he did so in the way most of his important decisions had always occurred: quietly, with minimal fanfare, and at a time when someone would later say, “Y’know, perhaps he shouldn’t have done that?” The obituary described him as “a local artist, writer, and curmudgeon of rare sensibilities.” That was accurate enough. The memorial was attended by people who had been mildly influenced by him. There were readings of his aphorisms (most of his anaphorisms were given a skip, however), an awkward toast was made, and someone played Ziggy’s guitar in the key of comfortable regret. Although, it must be said that rumours persist that Eliphas Plunk never really died at all—that he’s still out there somewhere, being ever so mildly alive. Miserable, but content. It was a closed casket, after all. Not because Eliphas had suffered any sort of ugly trauma, but because he had thought it would be better that way—so as not to disappoint his mourners.

Nevertheless, there is a kind of art in being persistently present without excess. Eliphas’s life was not a manifesto; it was a ledger of small entries. He taught some people how to sit with their doubt politely. He made others laugh by naming things they felt but could not say. He was, ultimately, less a hero than a witness: to middling joys, to laughable disasters, to the tiny economies of grief and pleasures that all go into making up a life.

IX. The Plunkian Condition

Scholars — who are paid to name what the rest of us muddle through without terms — eventually christened his particular blend of melancholic irony The Plunkian Condition. It denoted a mild, chronic persistence in the absence of decisive teleology. Think of it as endurance dressed in thrift-store finery. Think of someone who continually shows up to life with the polite pretense of interest and leaves before things get too complicated.

Collectors bought his blanks and called them triumphs in minimalism; students compiled his aphorisms into zines; some read him as a prophet of our era. Others read him as a sign that we are, in fact, fond of sorrows we can RSVP to. Either way, he stuck around in conversations like an old joke that keeps getting retold not because it’s funny, but because it’s easy to remember.

Author’s Note

Eliphas Plunk was invented by the cosmos to be a mirror for those who prefer understatement to spectacle. He survived on a diet of small failures and the occasional compliment, which is to say that he lived like so many of us do: not badly, not particularly well, but diligently enough to leave an outline. He was not noble and he never wanted to be; his work, if there was any, was the effective demonstration that continued attendance at one’s own life is itself a form of courage.

If you see something of him in yourself, take the compliment seriously. Pour something amber in hue, lower the lights, and allow yourself the modest luxury of being mildly alive for a spell. It is, under most circumstances, quite inadvisable but frequently hilarious—at least to an outside observer. And, I guess that’s worth something.

— D.